John D MacDonald was a family man. From every bit of biography available about the author it seems clear that he and his wife Dorothy had a near perfect marriage, and that they remained faithful to each other throughout the 52 years they were together. There were, of course, the three years that John served overseas during World War II, where long periods of absence caused many men to stray, and MacDonald may have also, but there is no evidence of this. Hugh Merrill, in his 2000 biography of JDM tried his best to make something out of a low grade fatal attraction between MacDonald and author Babs Deal, but the epistolary evidence he cites does more to argue against an actual physical affair than to make a case for it. With MacDonald engaged in an occupation where he sat at home all day, and with Dorothy herself not working, the chances for dalliance were few, even if either partner were so inclined, which they weren’t. The general consensus of observers throughout the years was that Dorothy was unfailingly supportive of her husband and that John practically worshiped his wife.

But adultery was never far from MacDonald’s mind, for how could it not be in the imagination of an author of popular fiction? In 1953 he had tackled the subject in both a McCall’s short story titled “Forever Yours,” and in his first mainstream hardcover novel Cancel All Our Vows. At that time he told an interviewer, "This is the first of a group of books, rather than a series, which deals with that specific jungle in our backyard -- that conflict between social mores and personal ethics in the American upper middle class. The focus of this novel is those 'critical years' when both men and women feel as lost and misunderstood as they did when they were children." These works, which MacDonald later referred to as his “manners and morals” novels, continued the following year with Contrary Pleasure and were then replaced by his more typical works of crime and suspense. Then, in late 1957 and 1958 he produced three works in this category, as if he were making up for lost time on this particular subject. The first was A Man of Affairs, which dealt principally with morality in the business world, and explored the responsibilities that corporate executives have to their companies, their stockholders, employees and to the communities they operate in. Third was Clemmie, and its subject was as much obsession as it was adultery. (Finally, in 1962, he wrote his final work in this vein, A Key To the Suite, arguably his finest novel.)

The second was The Deceivers, which came on the heels of his blockbuster novel The Executioners and which preceded Clemmie by two months. It is his second great adultery novel and is built on the pattern of his first, Cancel All Our Vows. Indeed, as he did with many of his works, The Deceivers seems to be to Cancel All Our Vows what The Empty Trap and (later) Clemmie are to 1951’s Weep For Me: a chance to improve on past failures, or at least what the author deemed failure.

The problem with Cancel All Our Vows is not that it is a bad novel but that it is an unfocused one. MacDonald, with his first big mainstream hardcover novel, tries to do too much and as a result dilutes the work’s impact. And he also seemed uneasy with the subject matter, to the point that he has both marriage partners (Fletcher and Jane Wyant) unfaithful to each other, first with Jane’s makeout-gone-too-far and later with Fletcher’s willful act of adultery. But MacDonald clearly saw Fletcher as the book’s protagonist, and by dealing so much with Jane’s actions, reactions and motivations it not only confuses matters, it seriously harms the novel’s plot. The author does not make that same mistake in The Deceivers.

Recall that in Cancel All Our Vows Fletcher and Jane Wyant are an upper-middle class suburban couple with young children, and Fletcher is an executive with fairly large corporation, a soon-to-be captain of industry. In the opening pages of the book we learn of Fletcher’s ennui and his gradual alienation from the values of suburbia. From his living room window he can see, in a faraway field, an old red barn, which becomes the symbol of his dissatisfaction. His underling at work, Ellas Corban, is also married with children, he to Laura, a woman who seems to have already arrived at the state of alienation that Fletcher is heading to. To put it succinctly, Ellas is an opportunistic backstabber at work, intent on getting Fletcher’s job any way he can. Laura, while not a complete succubus, is equally as manipulative as her husband in attracting Fletcher’s unspoken desires and working to consummate them. Jane is a good woman who made a terrible mistake.

In The Deceivers Fletcher is now Carl Garrett, a 42 year old, married with children suburbanite working in an executive position in a local corporation. But that is where the similarities end. His wife, the exceedingly domestic earth mother Joan, has neither the looks, athleticism or the inclination to be a Jane Wyant. The “other couple,” here next door neighbors, not co-workers (although there is an Ellas clone in the novel) are Bucky and Cindy Cable. Bucky is a strong, simple, athletic travelling salesman, while his wife Cindy is a toned down version of Laura Corban, someone who has rejected many of the suburban values that her husband aspires to, but who is less overt in her expression of them. The Cable’s are in their mid twenties, parents of two young children, and Cindy is beautiful, described lovingly as the MacDonald female archetype.

Cindy... was a tall girl of about twenty-six with dark blonde hair, long hair that she wore alternately in a ponytail, or a bun at the nape of her neck, or piled high. Her cheekbones were high, cheeks delicately hollow, gray-blue eyes set wide, mouth wide and soft, with a not unattractive hint of petulance. She moved slowly, and held herself well.

The two couples are warm friends who socialize a lot together, wander in and out of each other’s houses during the day, and are completely relaxed in each other’s company. MacDonald lays the groundwork for the eventual affair between Carl and Cindy in a lengthy section of Chapter 2 where Carl recalls the early days of the couples’ friendship. (The novel is told in third person limited.)

Cindy's mind was more like Carl's, yet more subtle, more oblique, more prone to dissect and be amused by the grotesqueries of life. And both he and Cindy were inclined to be pessimistic, frequently lethargic... Sometimes when the four of them were talking, Cindy and Carl would go bounding off the beaten track into one of their conversational games, projecting the customs and practices of [their suburban neighborhood] into exaggeration and absurdity, or making up new words to fit unique social situations, or establishing the platform of a new political party, a party which would outlaw cookouts, funny chef aprons, slacks on fat female picnickers, and meat which was charcoal on the outside and only slightly wounded in the middle... And then Bucky would look at Joan and say, "There they go again." And Carl would sense in Bucky and in Joan a slight hurt at being left out... Sometimes Cindy was able to look at an accepted situation from such a wry angle that Carl would suddenly see the absurdities of his own behavior and laugh with pure delight... Also, in Cindy, Carl saw those emotional factors which, in himself, had kept him from attaining the success in the business world which he might otherwise have achieved. A skepticism, a reluctance to conform, an appreciation of the ludicrous, had kept him from being thoroughly sold on the necessity for an unthinking devotion to the mighty ... Corporation...He knew he was considered something of a maverick, and he was aware of being passed over several times in the past so that more malleable, less skeptical, and less able men could be promoted... At times he felt wistful and half guilty about his inability to commit himself totally, but he justified and rationalized by telling himself that he had and was having a good life…

And at the end of Chapter 2 Carl has an interior monologue that amplifies his outsider status, as he looks toward the lights of the city he and his neighbors have chosen to live away from. It is as sharp and as bitter as any jeremiad dreamed up later by Travis McGee:

There were a lot of words for Hilton. Industrial complex. Lunch-bucket town. A forward-looking American city making a wise and valiant effort to solve its problems of traffic congestion, slum clearance, high taxes and high crime rate. Or, a vital clog [sic?] in the industrial might of America. Or, a rather inviting target for an atomic warhead. Or, a foul and grubby place to live and try to bring up kids, for God's sale, and keep them from running wild.

It was, he suspected, like all of the other cities in the heartland of America. Or maybe all of the cities of all time. Dedication mated to venality. Energy and progress linked to idleness and sin. But in this time, louder than ever before, rang out the plea that was more than half command -- AMUSE ME. Fill these sour hours of this, my one and only life, with the gut-buster joke, the rancid ranch-hand laments about love, the talcumed armpit and shaven crotch of commercial love, the flounderings and hootings and vomitings of the big bender. By God, I want the girlie shows and the sex books, and a big cigar is a sign of masculinity and success. I want to be slim without dieting, smart without half trying, rich without working. And I want to read all about it, read all about hell for the other guy -- with pics of him strewn on the highway, or cleaved with an axe, or being carried out of the mine. So I can hug old precious, invaluable, unique and irreplaceable me. Amuse me. That keeps me rolling along, boy. So I can live without dying and right at the end of my world, die without thinking. Then all the rest of you can go to hell because I won't be here, and by God, when I was here, I had it good. I had it sweet and hot and often.

The opportunity arises at the beginning of the summer. Joan goes into the hospital for a scheduled operation and Bucky will be gone on an extended business trip. The Garrett children are away at camp and the younger Cable kids have been sent to stay with their paternal grandparents for the summer. Both Carl and Cindy will be alone in their respective homes. There is no hint of any kind of a sexual attraction between the two early in the novel, and even when something does happen, it's uncertain exactly what is going on and what spurred it. On Carl’s first night alone he wanders out into his backyard and up to the western border of his property to a maple tree he had planted years ago. (It’s one of the novel’s central symbols, in the same way the red barn was in Cancel All Our Vows.) He looks over at the Cable’s house and sees Cindy sitting alone in her kitchen and invites himself in. There is nothing ulterior hinted at in this action, as it has been established that this was common practice with these two families. And at first nothing does happen this first evening, other than these two intellectually observant individuals having a typically intellectual conversation about how they “both despise certain aspects of [life in suburbia]. But then the conversation drifts into Cindy’s problems with Bucky, something Carl and everyone else was completely ignorant of. She reveals that she has “fallen out of love” with her husband, that she had had an affair before meeting Bucky and that her marriage to him was a “rebound situation,” and that Bucky has, for the last year or so, been engaged in a series of “cheap little affairs.” Wow! That’s more than Carl bargained for when all he wanted to do was share a beer with his next door neighbor. Cindy’s confession ends in tears and with Carl unable to think of any way to console her. He goes home and as he goes to sleep he recalls his early days with Joan, and later realizes that it is a defense mechanism to help him from thinking about Cindy Cable. The seed has been planted.

The following evening the scales fall. Once again Carl wanders over to the Cable’s house, but this time when he knocks at the back door he hears the sound of the shower running.

In that instant he visualized her so clearly and so perfectly that he might have been staring into the shower stall rather than into that particular corner of his mind. He saw her long flanks and the secret curvings of her and the soapy freshness, the cones of abrupt breasts, and the belly's gentle convexity and the long complex curve of her back and the wiry pyramid of pubic hair between satin thighs. In the instant of his visualization desire came to him, savage and ready, and he knew that it was not new. He knew that it had been with him for a long time, and that he had never permitted himself to accept it, to even be consciously aware of it. He thought of all the times he had looked at her, very calmly and casually and thought, Cindy is a damn good-looking woman. There was no ordinance against making such an observation, against admiring her objectively, or enjoying being with her and talking to her. And because desire had been so long suppressed, it had a violence that startled him.

So after another couple of beers and conversation, Carl uses a stumble as a means to kiss his neighbor, and Cindy responds. Then we get several pages of intellectual rationalization about how they both had wanted each other for months, but we mustn’t go there, it’s so cheap and obvious, we can’t open this pandora’s box. But the box has been opened, and after they go back to their respective homes agreeing to try and forget the whole thing (the kiss), Carl can not get her out of his mind.

The next afternoon it is Cindy’s turn to come over to the Garrett house, and after much back and forth (really, how much can these characters talk about this?), Carl grabs Cindy on the living room sofa and violently disrobes her. Their affair is about to be consummated when Cindy fights him off and puts a stop to the action. The reason? “Not here. My God, darling, not here, not like this.”

So after many more rationalizations they decide to "wear it out. Have a perfect glut of each other. Sicken each other." In other words, arrange for a motel room somewhere far enough away and have at it for three days. They agree on a time and a place and Cindy leaves for her own home. But before she does she asks Carl to do something.

"... before we start... I want you to say one thing to me. You can call it a rationalization if you want. It probably is. But I want to hear it said. You only have to say it once, if it's going to be too hard a lie to say."

"I love you, Cindy."

"And I love you, Carl. Was it hard to say?"

"Very easy to say. I'll keep on saying it."

This exchange does much to illustrate the differing motives of these individuals. Carl has to be asked to express his “love,” for his need for Cindy, born of opportunity, is little more than an “animal” hunger, a way to assuage the aimlessness he feels in life and (especially) at work. The novel’s parallel plotline concerns Carl’s role as corporate executive, and how the undemanding nature of what he does has caused a listlessness in his performance that he is only dimly aware of. Cindy, on the other hand, comes to the affair in need of something more basic, a freedom to express herself outside of the suburban ethos that the two of them must follow. She doesn’t really want love, per say, but for Carl to tell her he loves her. But in addition for her need to revolt against the rules of suburbia, she has a genuine need for permanence, and after the night in the motel she falls hard for Carl and begins dreaming of a life together.

Carl’s wife Joan is, of course, not completely forgotten, and the near trysts with Cindy up to this point are played out in counterpoint to Carl’s very domestic visits to Joan’s bedside. Unfortunately they read as very boring scenes compared to the drama taking place at home. The motel is reserved and clandestine arrangements are made for the two to arrive separately. Everything goes according to plan and the affair is consummated, but small problems begin to arise. That first night while Carl and Cindy are at the motel, Bucky calls home at night and gets no answer. Worried that something is amiss, he calls the Garrett house and, again, gets no answer. He calls another neighbor, who he convinces to get up and go over and check on Cindy. He reports back that the house was dark and that Cindy’s car was not in the driveway. Then, Carl has to lie to Joan about switching a dinner engagement that was set for one of the planned motel nights, and in order to hide his lie he has to recruit a smarmy real estate agent and acquaintance to cover for him, bringing him in on what is going on without naming names. Finally, 26-year old Cindy is wearing Carl out in bed, her “shockingly impressive” desires threatening him to wear him down to a nub. She begins acting like a newlywed, ebullient and radiant, and the two agree to extend their stay at the motel to four days.

As Carl begins to feel real guilt about the affair, Cindy’s guilt disappears. Then, the expected result -- expected by the reader certainly, but not by Carl, who is blindsided. During dinner Cindy tells Carl she wants to tell him something, and that there can be no discussion of it until after their upcoming third night of sex at the motel. She begins her speech directly: “I love you and I want to be married to you.”

Without revealing anything more, it won’t spoil the novel for the potential reader for me to say that things go downhill from here. In MacDonald’s moral universe how could it not? Sin is punished, lives are upended, and there’s even a realistic bit of violence. Carl is changed, Cindy is changed, everyone in their immediate orbit is changed, and the comfortable little world they resided in is gone forever. Carl and Cindy’s resentments of the mores of 1950’s suburban America have been tested and are utterly repulsed. And like Fletcher and Jane Wyant, the future for these people is left in complete doubt at the end of the book.

It is unknown to me if John D MacDonald attempted to have The Deceivers published in hardcover, but it certainly reads like an “important” mainstream novel of the time. As it was, the paperback original that saw its initial release seems to have been completely ignored by contemporary reviewers. JDM bibliographer Walter Shine could locate no reviews of the first edition, and only one when the novel was republished by Fawcett, and that one appeared in the Dublin, Ireland Herald. The uncredited reviewer wrote, “MacDonald has built up a dramatic story of the fall from grace of a happily married man… This is a tale of hypnotic attraction and remorse, of domestic treachery and its unfailing sequel of unhappiness and insecurity.”

Dell published The Deceivers in two printings, first in May 1958 and later in August of that same year, for a total run of 195,000 copies. This was pretty much in line with the number of copies of A Man of Affairs they published only a few months earlier, but actual numbers for that book were not available to Shine when he compiled his Potpourri. Fawcett, as they did with nearly all of the JDM titles, reprinted the novel in 1965 and their versions went through nine different printings. In 2010 the eBook was made available.

The cover for the Dell First Edition was illustrated by Mitchell Hooks, the second of three JDM paperback titles he would illustrate. His first was the iconic A Bullet for Cinderella, one of the most recognizable paperback covers of the 1950’s, and his work on The Deceivers is done in a completely different style and is, unfortunately, nowhere near as good. It pictures an accurately realized Carl and Cindy embracing.The first four Fawcett editions features another, more distant depiction of the couple, again accurately depicted, illustrated by an unknown artist. The cover blurb goes, “They were two nice people who hated themselves for what they were doing -- and tried to call it love.” The last five editions were done by Robert McGinnis and his illustration depicts a decidedly younger looking Cindy and Carl with clothing more representative of the 1960’s. Surprisingly, there is no William Schmidt cover for The Deceivers.

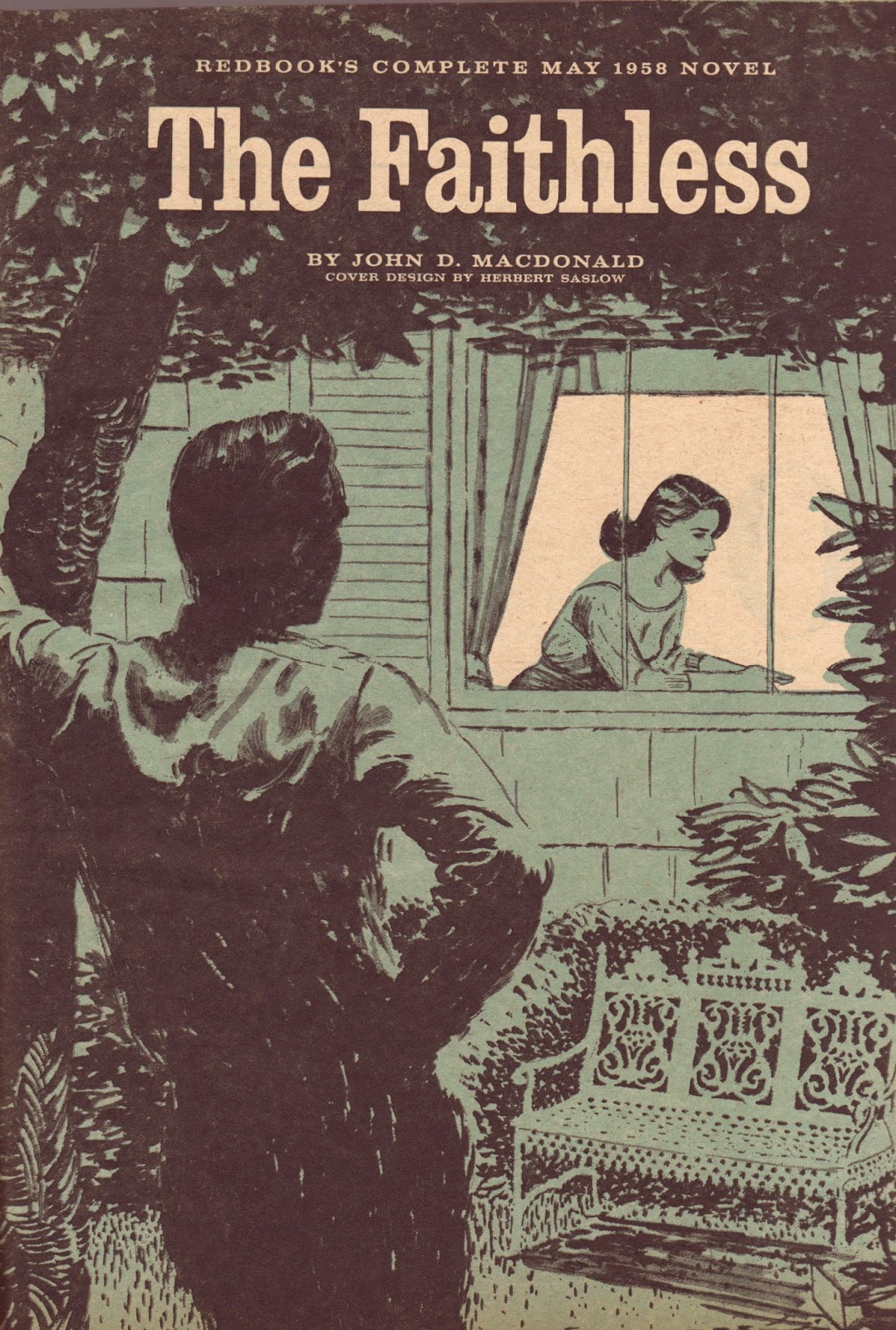

The same month that The Deceivers was published by Dell it also appeared on newsstands as the monthly “Complete” novel in the May 1958 issue of Redbook magazine. Under MacDonald’s original title for the work -- “The Faithless” -- it was a typically truncated version of the original with some changes here and there. One of those changes was major: “The Faithless” begins at a point after The Deceivers ends, answering one of the major questions left unanswered in the novel. It is entirely in keeping with the spirit and flow of the story and not at all out of place. One wonders if it was intended for the book version but eliminated by a Dell editor.

There is, of course, the elimination of a lot of the wonderful detail that makes MacDonald novels sing and a lot of beautiful background work gone in the interest of brevity. There are many little changes here and there -- like Carl having a younger sister in the book but being an only child in the magazine version; Joan as a college student when she met Carl in “The Faithless” but working at that time in the book; Cindy having an affair prior to her marriage to Bucky in the book but had only a “relationship that messed her up emotionally” in the magazine. But credit must be given to Redbook -- specifically its Senior Editor William B Hart -- for publishing what they did, for “The Faithless” is a long magazine novel indeed, and its subject matter may have raised more than a few eyebrows among the magazine’s “young adult” audience, even in 1958. The monthly notes on the masthead page features a photo of JDM with Hart at a hotel in Cuernavaca, where the MacDonald’s were living for the extended winter of 1957 - 1958.

I mentioned in opening that John and Dorothy were quite secure in their marriage of over a half a century and there is no credible evidence that John ever strayed. The Deceivers is a work of fiction, complete with the standard disclaimer (“This is a work of fiction, and all names, characters and events in the story are fictional…”) on the copyright page of each edition. But it was a fact that MacDonald occasionally gave his fictional characters bits of background that closely mirrored his own. Think of all of the stand-ins for his hometown of Utica, or the lake settings based on his summer home, or the backgrounds of the professional men, and especially the sheer number of characters who served in the military during World War II in the China Burma India theater of war. Andy McClintock in Dead Low Tide was a Syracuse University graduate, as was MacDonald. Sam Bowden in The Executioners served in CBI Theater of War in WWII, as did MacDonald. Lee Bronson in The Price of Murder was discharged from the Army at Ft. Dix, as was MacDonald.

But I think I’m pretty safe in stating that there is no one character in all of MacDonald’s writing that has so many of the author’s background similarities as Carl Garrett. Just look at this list:

Carl’s father expects that his son will follow him into his business and is surprised and disappointed when he decides to take a different path; Eugene MacDonald expected his son to follow him into a business career and was unhappy that he did not. (Interestingly, Carl’s choice of careers was the one the elder MacDonald wanted for his son.)

Carl’s hometown is Youngstown, Ohio; MacDonald’s was Sharon, Pennsylvania, a small town 15 miles outside of Youngstown and now considered a suburb of the larger city.

Carl served in the military during the war, received orders in March 1943 to report to the CBI Theater and was eventually stationed in New Delhi, India; JDM, already in the military when the war broke out, was ordered to CBI in May 1943 and was stationed in New Delhi.

In the magazine version of the novel, Carl and Joan honeymoon in a rented cabin on the shores of Lake Piseco in Hamilton County, New York: John and Dorothy Prentiss MacDonald honeymooned in the Prentiss family cabin on the shores of Lake Piseco, where the couple was later to purchase land which would become their summer home for the rest of their lives.

What to make of all this? Is this intentional subtext, a red herring or an author going overboard in picking out pieces of his own past to flesh out a fictional character? The bullet points above are the similarities we know about, thanks to a 40 year career that has been documented in numerous biographical works, none of which were available to the general public in 1958. What about similarities we don’t know about? And what was the point in drawing on so much of his own past and characteristics to create Carl Garrett, an adulterer?

The tabloid answer to these questions is that The Deceivers may have been MacDonald’s meditation on and atonement for a past indiscretion, a sin committed sometime after he was married and hidden from everyone but (perhaps) his own wife. This is, of course, sheer speculation on my part, a fan knowledgeable of the author’s biography and curious as to why in this novel -- of all his novels -- he created a character so similar to himself. As mentioned above, there is absolutely no evidence for this supposed dalliance, and if there was any in the JDM archives it most certainly would have come to light in Merrill’s research for his 2000 biography. He was certainly looking for something.

But these suspicions put one part of the book in a completely different light, a flashback Carl recalls of his wartime years. It was, before Cindy, his only adulterous affair and it took place in New Delhi, a result (he presumes) of his new state of isolation and loneliness. The female involved was one Sandara Lahl Hotchkiss, a mixed-blood chi-chi who worked at CBI Headquarters as a civilian. He met her at a dance and on their first date he “possessed her” in her small apartment. Carl recalls “Sandy” as “coarse,” “arrogant,” “selfish,” “quarrelsome,” and “demanding,” but also "completely and compulsively sexual, inventive, demanding and experimental, shameless and greedy and aggressive, insatiable and bold” in bed. The affair went on for over eight months and Carl recalls the spell she cast over him as a kind of “sickness,” that he was unable to resist. During this period Joan’s letters took on a "remote" feeling and Carl's own letter writing back home nearly ceased. The affair ended suddenly, one Sunday morning during a post-coiatal observation of the sleeping Sandy, where Carl suddenly becomes "so strongly repelled that his stomach twisted and he thought he would be ill." After several weeks of resisting returning to her "spell of evil," Carl gradually comes to his senses, begins to write to Joan again and is, mercifully, transferred to a different post.

Not only does this vignette contain several more links to MacDonald’s own past, it is nearly identical to the story that started his writing career, “Interlude in India,” the famous letter that he wrote home to Dorothy MacDonald and that she submitted for publication. The descriptions of Sandy are, in some cases, word-for-word retellings of her counterpart in the short story, Sal, including her “bright black hair,” “sallow” colored skin, her mixed blood and the smell of stale spices on her breath. Not to mention her temperament.

Was MacDonald secretly revealing a story from his own past, in both works of fiction? I know, writing home to your wife about having an affair with a local Indian girl seems outrageous, but both stories end with the officer dumping the young lady, resulting in a newfound sense of freedom. It is something that has always intrigued me, and I could put it off to nothing more than prurient thinking had not the author made Carl Garrett so recognizably HIM.

* * *

Finally (I promise) there is a bit of conversation in The Deceivers between Carl and Cindy that takes place on the third and fateful afternoon in the Garrett house, where in attempting to intellectualize the duo’s mutual attraction, Cindy makes the near fatal mistake of uttering the “D Word”:

"Birds of a feather," [Cindy} said.

"The undeniable attraction of nonenties."

"Don't call us that. Anything but that, darl ... darling." And she looked defiant.

He laughed aloud.

"What's so damn hilarious?” she asked heatedly.

"... I was laughing at myself as well as at you. You don't go around calling people darling. But you started to call me darling. You got halfway into the work, not knowing why you started to say it, and then wished you hadn't stopped, which made it overly obvious, and then decided that rather than cover up you'd better go through with it, and so you did, and then, to cap it, you sort of glared at me as if daring me to make anything out of it, daring me to find any significance in it."

She flushed and said, "We're so hopelessly complicated, Carl... I don't know where the darling came from."

As regular readers of John D MacDonald know full well, “darling” was his favorite term of endearment. And in The Deceivers the “darling” count is off the charts.

The Deceivers is available as an eBook from Amazon, Barnes & Noble, and wherever else you buy eBooks. Used paperback copies aren’t too hard to locate either.